In the early days, I described The Design Office by what it wasn’t: “It’s not a design firm.” Starting a service-oriented firm is the customary path for a designer. Graphic Design is colloquially explained as the intersection of art and business. By describing The Design Office as “not a firm,” I hoped to situate the group primarily in the arts. Until we retired our phone line two years ago, The Design Office was listed in the “arts organizations” section of the Providence Yellow Pages.

“It’s graduate school for the rest of your life,” worked well as an answer until recently. This answer assumed that who I was speaking to attended an MFA program in design or might have a positive association with graduate education. Graduate school attracts motivated practitioners that question conventions and chart new territory. They share space and resources, but create independent bodies of work. I was only three years out of the Yale MFA program when I started The D.O, and I was hoping the framing of the Office as graduate school for life would help manifest a community similar to my peers from Yale.

This answer worked for a while, but The D.O. feels less like graduate school now. This is to the credit of Sarah Rainwater, Nic Schumann, and Greg Nemes, who have grown their independent practices into small businesses. The D.O. at age ten also houses The Morisawa Drawing Office, another three-person company. There are more business concerns raised on the 3rd floor of 204 Westminster than graduate school conversations. We even have a water cooler. It’s also rare to see people working at night, or on weekends. Working at the graduate school pace is hard to sustain it turns out — so I don’t use it to explain what The D.O. is anymore.

Another way I describe The D.O. is as “a zero-profit organization that supports designers.” This can be shortened to: “it’s a support system for designers.” The term zero profit aligns it with non-profits, but it’s not formally a non-profit. It’s primarily member funded and does not earn any profits. Membership dues pay for common needs: equipment, furniture, and events. Another critical need is labor: running the space is done on trade, as are infrastructure projects, upkeep and basic management. Membership dues fund more than the basic expenses though—they are a shared investment in each other. I hope that The D.O. supports more than just the current membership as well—through advocating for a certain type of design, through collective action.

The term “collective” is a good term, too, but I rarely use it to describe The Office. Collectives are often a set number of people with a set agenda. Our members share more values than not, but they don’t often operate as one. Collaborations occur — we are co-located, but The Design Office rarely authors work as a collective body. “Co-op” is not an apt description because the ownership isn’t shared.

Nevermind the fact that The D.O. is a co-working space—and there is certainly a demand for and awareness of co-working spaces. But I don’t feel comfortable describing The D.O. solely as a co-working space because of the negative connotations with co-working spaces in the creative community. Designer Jason Alejandro mentioned us in a tweet and wrote we were “a co-working space, but not in a bad way.” Ben Shaykin picked up on that immediately, and it was part of our Twitter bio for awhile. If I describe The D.O. as a co-working space, I usually say “it’s a curated co-working space.” This is true, and more nuanced. We have an application process that requests a resume, website of work, and paragraph with reasons for wanting to join. Existing members meet prospective members, and there’s essentially a vote. The curated nature of it assures the continuity in the workspace, prevents quick changes and invests current members in the process.

In terms of how we publicly explain ourselves, we’ve had three websites—each with their own taglines. In 2008, we used: “a place where individuals work together.” This was followed in 2012 by: “a place for independent designers in downtown Providence.” The current version, dating back to 2015, reads: “a shared workspace in downtown Providence, RI.” The first and third embrace more disciplines than design. The space is set up for designers, and best serves designers, but it has benefitted from the presence of programmers, photographers and other non-designers. We have always listed current members and there is always the potential for new disciplines to emerge from who is here or who enters the room.

At times the members themselves wonder what The Design Office is, and what holds it together. We have done a variety of things over the years. What I return to over and over again (physically and metaphorically) is the space itself. It is possible to work on a laptop at home or at a coffee shop or on a train. But if you’re a designer, you will inevitably want to plug in and focus for awhile. The Design Office should be the best place to get work done. It has shelves of books for research and inspiration. It has equipment: printers, scanners, rulers and cutting mats. It has custom-designed desks, tables, a phone booth. It has high ceilings, good light, historic retail architecture and is in the city center. And most importantly, it has thoughtful, hardworking, self-directed people. As the option to not be adjacent to others becomes easier and easier, the need for humans to share a room together becomes greater and greater—and that’s what The Office is best designed to do.

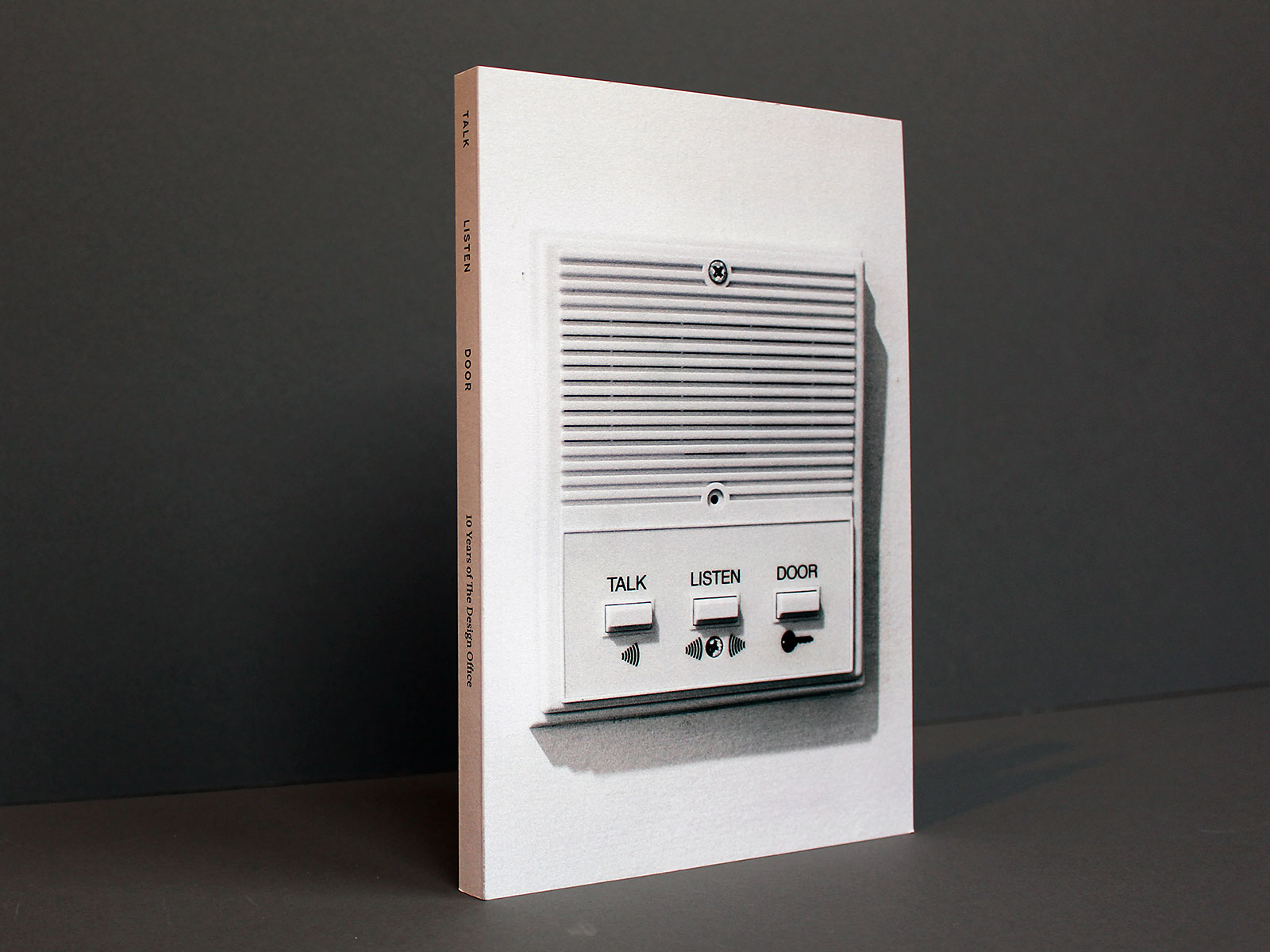

This essay appears on pages 23 – 25 in the book, Talk Listen Door, available for purchase from Draw Down Books.